Allocation Systems

Alternative allocation has always been a fascinating concept to me. The insight that resources can be allocated in different ways is central to the fundamental theme of economics: choice. I used to think that economic choice was equivalent to the concept of economic scarcity. However, discussing allocation systems made me realise that this may not be that obvious.

To explain this, I first want to clarify the concept of an allocation system. What an allocation system does, I believe, is three things. It addresses three questions: How are resources allocated? How is it decided what to produce?, and how is production distributed? These three questions sum up the fundamentals of economic choice.

In most textbooks these questions are not made explicit. But if we want to understand economics, we have to ask these questions. Moreover, we have to evaluate how possible allocation systems apply to these questions. To do this in a 21st century economics education, I would suggest to focus on three allocation systems: the commons, the hierarchical structure and the market.

The term commons describes situations where resources are held in common by a community which governs them through informal norms and social practices. Commons are often associated with natural resources such as grasslands, fisheries and forests. It makes me think of the example of a community garden where the neighbouring households have to decide on its use. Some would like to use it as a vegetable garden or a food forest, others would like to keep some chicken or separate part of the garden as a sheep or goat pen, some would love to shape a flower garden with picnic areas, a place for nothing else but to enjoy the sun and the outside, households with children are likely to ask for room to play, maybe a small football pitch, and dog owners could see it as a perfect place to ‘walk’ their dogs.

What you can see from this example is that the resource is a given. However, what is to be produced with the resource, in terms of services, as in the example, or goods, is not. Is it going to be a garden for dogs to do their needs or a flower garden that would be on equal footing with a Royal Horticultural Society garden? Who is going to do the work required? And who is going to enjoy the fruits of the garden? Which is another way of asking how its services are going to be distributed across the neighbouring households. In a 21st century economics education we could teach students how to arrive at the informal norms and social practices so that community gardens could become more than the stretches of grass I have encountered so far, because people could not arrive at a common ground.

Markets are at the other end of the spectrum, where resources are not a given, but needs are. Companies operating in markets are commonly hierarchical by nature and generally plan their production volume ahead of time. However with the rise of data science, larger companies are better able to predict their turnover and have shifted towards rolling forecasts. How well they are able to adapt to changes in their outlook, depends on their flexibility. What is the changeover time of their machines? How fast can they scale down or scale up? Are they able to keep raw materials, components or (semi)-finished products in stock to function as a buffer? Will they be able to fulfill the changed need for raw materials and other production factors?

Thus, the allocation of resources is derived from needs, as is the answer to the question what to produce, while distribution is done through the price mechanism of markets. Obviously there is much more to comment on this, but I will not go into market failure, as I did not go into the tragedy of the commons. I will leave this with two remarks: One is that the level of competitiveness of markets impacts the distribution of market power and its outcomes. Second is that, especially large companies, are able to shape needs through marketing activities.

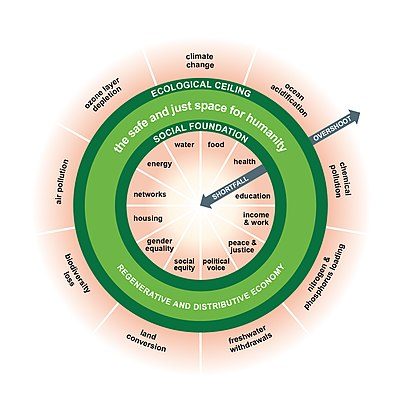

I would like to point out at this stage that the commons are based on resources, and I would therefore place them on the ecological ceiling, whereas markets are based on needs, which is why I would place them closer to the social foundation. Doing that, I am fully aware that markets where market power is concentrated are often the cause of a shortfall of the social foundation. Concentration of market power is, however, an example of market failure.

For now, this leaves me with the hierarchical structure, also known as planned economy, which was covered in the textbooks I know, in relation to the demise of the Sovjet Union and other communist countries. The hierarchical structure, however, is not uncommon. As I mentioned above, most companies are hierarchically structured. In practice we often see economic systems that are a combination of the three, even in economies that we see as a typical example of a market economy or a hierarchy.

In several countries in the Americas, for example, part of the land has been returned to its indigenuous people as compensation for the damage done to these people. Many indigenuous tribes treat the land as a commons. Most countries have a defense organisation that is hierarchically structured, with the countries’ president or prime or defense minister first in command. And then there is the market system, defined by its level of competitiveness.

In theory, the hierarchical structure is the hub between all questions. When a central management makes all the decisions about how to allocate resources, both to the present and the future, what to produce and how to distribute, it could weigh all implications. Balance both ecological ceiling and social foundation. However, there are also ample examples of failure of central management, on the level of companies, and on the level of governments.

So, when discussing allocation systems we need to address which of the three questions is most in focus, and what this implies for our goal: a social foundation for all while staying within the planetary boundaries.

When we look at the real economy it is clear that we do not have to choose one allocation system for the whole economy. In fact, the allocation system you’ll find depends on the perspective you take. In principle, everywhere people need to answer one or all of the above questions, they use some kind of allocation system. How does a household choose, for example? Decisions about the allocation of living space are likely hierarchical in a family with small children, but the living space could also be treated as a commons in a family with larger or no children.

With this discussion, I hope I have shifted perspectives on allocation systems and economic choice a little. There is much more to understand about this topic, so I am likely to return to this topic in the future.

henny@21steconomics.org – You can also find me on LinkedIn