A few days ago it was pointed out to us that the doughnut was not a model but a normative framework. Since we believe it is extremely important to teach young people the difference between normative and positive statements, this is an important insight. Therefore, it will not surprise you that we are very much aware of this. This is actually the reason why we prefer to say a 21st century economics education should be based on the doughnut framework.

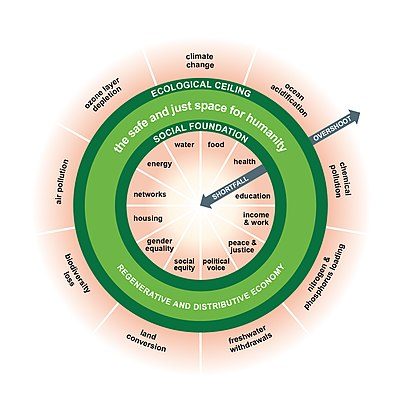

We believe that no matter how you design an education, it will be normative one way or another. The advantage of the doughnut framework as represented in the picture is that it is made very explicit and visible what the norm is. Moreover, the doughnut is based on the sustainable development goals of the United Nations and has been, as such, supported by most nations in the world as a set of shared values across the globe. By giving it center stage in an economics education we keep ourselves aware of this.

It also allows for some interesting discussion in the classroom, because how would the framework look if we let out planetary boundaries? Would this mean we would focus completely on wellbeing for all, with disregard for the earth? What if we removed the social foundation? Would this mean that all the riches of the earth can go to a few and the rest can fall apart for all they care? What if there are no boundaries at all? Or if we cherry picked some of the elements and left others out? I believe a discussion like this would improve appreciation of the concept of normative statements.

The other thing that came up in the same conversation was that it is difficult to place all the different flavours of economics within this framework. I do not believe it is that hard. Feminist economics, for example, is in fact part of the normative framework of the doughnut, rooted in the element gender equality. Complexity economics contributes a more systemic approach to an economics education. Ecological economics has a strong handhold in the ecological ceiling. Institutional economics inspires us to cover some real world economics when we discuss institutions and regulations that shape our economic system. Economic anthropology studies, for example, LETS systems and their impact on communities. Economic geography can help us understand dynamics in the world that are related to, for example, the location of natural resources. Political economy touches on the normative aspect of economics with which I started this post. Structuralist economics can help us understand differences in the rate of development between countries, and behavioural economics allows us to better understand economic agents. I could go on, but I leave it here.

I must admit that some economic schools and theories may have a harder time fitting in the doughnut framework. Some might be useful to clarify why our economies have a tendency to move outside the donut boundaries. Some economics schools can shed a light on which allocation systems to choose and the role of the government, but doing so within the framework might pose a challenge. A challenge I hope will be embraced, because how they are able to address the economic goal of the 21st century, to stay within the doughnut, will very much decide their future relevancy.

henny@21steconomics.org – You can also find me on LinkedIn